Thank you for reading these posts. I am looking back at some of the research I did for Constructing a Witch (Bloodaxe 2024), so search back on Substack if you’d like to see more.

For my last collection The Anatomical Venus (Bloodaxe 2019), I read swathes of the misogynistic and frankly bizarre treatise Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of the Witches), originally written by Heinrich Kramer. When the Malleus was first published, it was condemned by top theologians of the Inquisition who declared it inconsistent with Roman Catholic doctrines of demonology. The Malleus never went away though, Jacob Sprenger was added as an author in 1519 and it was revived by royal courts during the Renaissance as a tool to persecute witchcraft. In Fearless Wives and Frightened Shrews: The Construction of the Witch in Early Modern Germany, Sigrid Brauner cites the Malleus as the turning point in the perception of witches as being mostly women. Women being more evil of nature, more susceptible to the wiles of the Devil, generally weaker of spirit and body, and of course, sexually ravenous.

The book is oftentimes described as a kind of manual for any witch hunter out there who wanted to earn a living. The self-proclaimed ‘Witchfinder General’ Matthew Hopkins and his accomplice John Stearne set themselves up as witch finders and travelled around East Anglia from 1645-1646 torturing and hanging people for a wage. They were among the many people who took advantage of the climate of fear and unrest during the English Civil War. Contrary to the film The Witchfinder General, in which a fifty-seven year old Vincent Price plays Hopkins, Matthew Hopkins was in fact in his early twenties. He was the fourth son of a Puritan clergyman and it’s likely that he was home-educated. There is no actual evidence that Hopkins would have read Malleus, but it was a widely read book of the time, as was King James’ Daemonologie (1597) which Hopkins cited in his own publication The Discovery of Witches (1647). The records at Stowmarket show Hopkins’ and Stearne’s costs charged to the town to have been £23 (about five thousand pounds, these days) plus travelling expenses. I didn’t write anything about being a witch hunter as a career choice in that book, but I kept in on hold in my head.

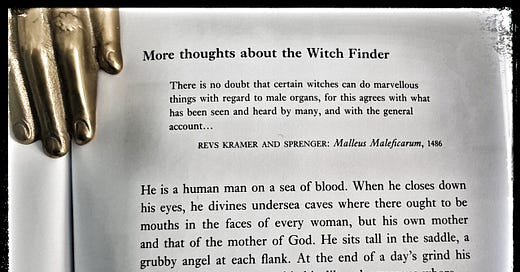

The quote from the Malleus I used for this poem is laced with the kind of paranoia, fear and desire the whole book is made of. Another quote being:

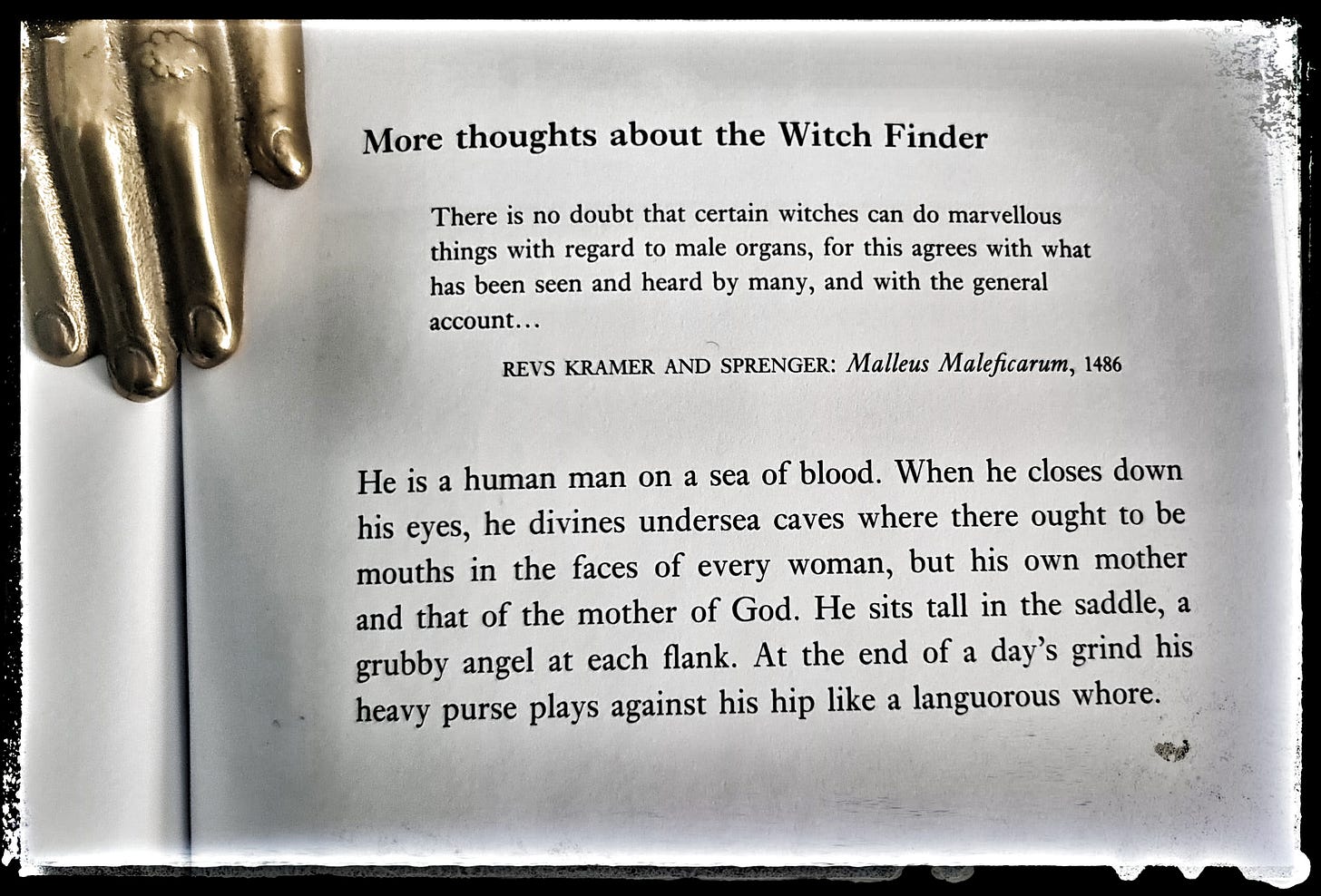

[W]hat shall we think about those witches who somehow take members in large numbers—twenty or thirty—and shut them up together in a birds’ nest or some box, where they move about like living members, eating oats or other feed? This has been seen by many and is a matter of common talk. It is said that it is all done by devil’s work and illusion, for the senses of those who see [the penises] are deluded in the way we have said.

And here is an illustration of a woman with a nest of penises in a tree. Perhaps ‘ a matter of common talk’ if somebody made a drawing about it in the margins of a medieval poetry book. But who actually saw this spectacle in real life, I wonder. Phrases like that and ‘with general account’, sounds to me that he is grossly exaggerating to collect ballast in order to bolster his position.

Marginalia en Roman de la Rose from Wikimedia Commons

Interpretations of this include that witches are the cause of erectile disfunction or that they emasculate a man in some other way. The penis is the focus though, even if the emasculation is metaphorical - a woman perhaps being more articulate or skilled at something than a man? An independent or powerful woman? A woman having no sexual interest in a man in particular, or men in general? These days of course, we have incels (involuntary celibates) with their own misogynist gurus across the manosphere radicalising boys and young men. Plus ça change.

(Please ‘like’ this post, if you do like it. I need the dopamine hit! )

Love this. People don’t realise how much research goes into writing poetry. ❤️